Mais de 5.000 itens colecionáveis diferentes, compre com confiança

Mais de 5.000 itens colecionáveis diferentes, compre com confiança

Stock Code : 001919

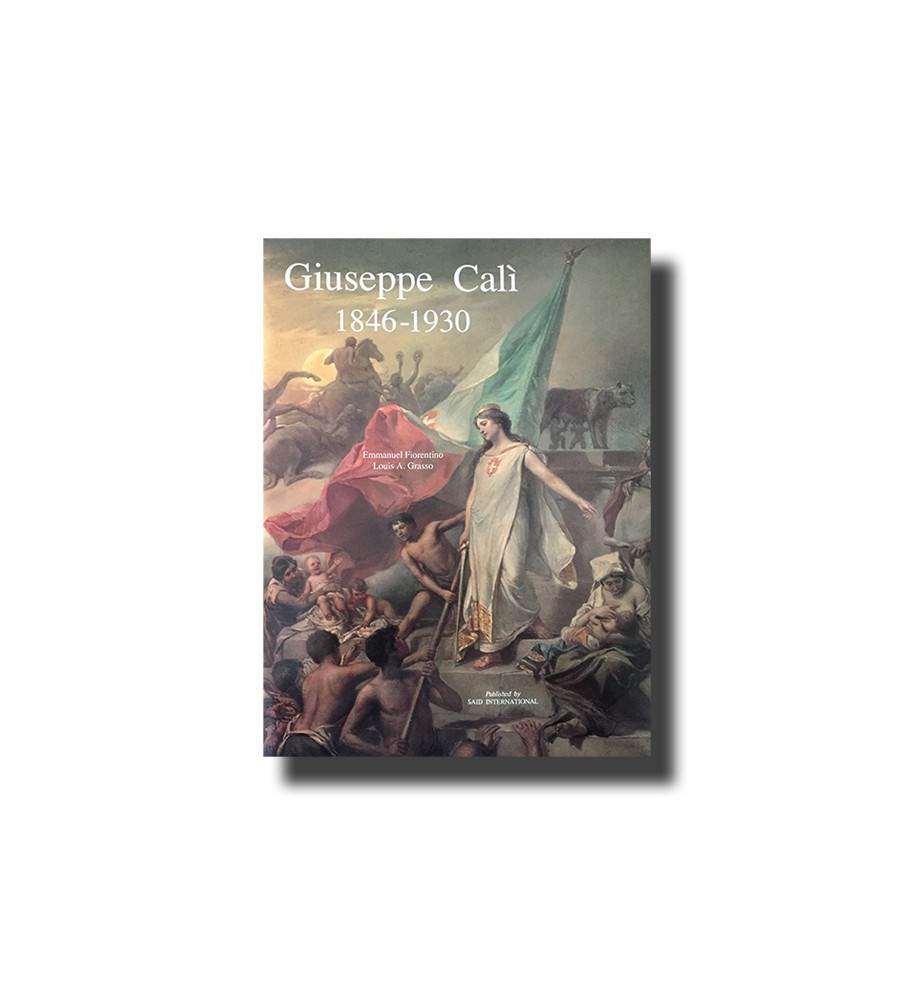

Giuseppe Cali' (1846 - 1930)

GIUSEPPE CALI 1846 – 1930 FOREWORD Art collectors and critics are often fortunate in being able to look at an item, and, because of a number of rules they use, they find they can sometimes assess it more or less correctly. Others will look at, say, a picture not knowing why they are enamored of it, or even possibly stricken by it: “I don’t understand, but I like it!” they say. Giuseppe Cali’s work, the subject of this book, is easily likeable. It is essentially ‘art for the people’; when he is solemn, we bow our heads with him; when he is sad, we grieve with him; when he is happy we rejoice, when he is pretty we coo and when he is amusing, we smile with him. This said, his work is hardly propagandist or even remotely political. Cali is a talented craftsman within the establishment, but much more, and what a happy and fulsome graduation so to speak, he is also blessed with being gifted. This is a man who would have achieved reputation if he had been self-taught, but as the authors will tell you, his training was thorough for its day, and broad well beyond the perimeter of the little island home which claims this Maltese titan for its shores. Giuseppe Cali deserves some study. When the obvious is relished by us mortals, there is more for the trained eye. Like the poet who chops and changes until he has achieved the correct formula, so does Cali’s work achieve polish and balance. There are the bread-and-butter works; the drawing-room pieces of genre and portraiture; the tedious things, some done in a hurry to achieve a dateline for perhaps a parish priest: and all together, there is the vast volume of his opus which reflects his tenacity to keep hunger from his front door. We can see Cali a tremendous capacity for work under pressure. On closer examination, what always raises its head is quality. This happens because he was a master. His unhurried work, his dedicated and enthused upon work, and his inspirations all have, in differing doses, that angelic ingredient which is quality: the quality of his technique, and the quality of his perceptive eye and, where he is not constrained by his brief within a dome or apse, the quality of his composition. All this must be considered carefully before judging Giuseppe Cali. Here is a great man whose ability and virtuosity we need not question. Why question his ability by assessing his lesser works? Let us instead contemplate the St Dominic altarpiece in the Parish Church of Port Salvo in Valletta; the Prophets in Mosta; the portraits of Negotiante Agostino Cassar Torreggiani and Giudice Carbone; the Tre Rome with its hidden pentimenti and ultimate polish; the Apothesis of St Francis, the Death of St Francis also in the church of the same name in Valletta; the Bacio di Juda; both St Jerome and St Lawrence at the Sacro Cuor in Sliema, even his youthful Death of Dragut, and then consider an assessment. We cannot make a comparison, because as a Victorian Maltese artist Cali tends to stand alone, but set among his peers in Europe, he stands fair and even proud. The late Dr Herbert Ganado writing at the time of the Centenary Exhibition organized at the Palazzo de La Salle by Rafel Bonnici Cali says in an article in Lehen is-Sewwa that had Cali continued his studies in Rome, which he very much wanted to do, he would have been one of the ‘greats’ of his time. I feel that had he gone to Rome and developed a more international and daring sophistication opting perhaps for the style of a pre-Raphaelite or Impressionist, he would not necessarily have been the better artist. I do not think that after Naples he was blinkered from the various are movements active or fashionable in Europe. Malta was never provincial; artists on their Overland Route were passing through the whole time. I believe that there was opportunity for artistic intercourse if one was interested in, or in need of, new direction. Certainly Cali’s reputation has suffered from underexposure abroad: he is not even listed among the masses of artists in the eight volumes of Benezit. The last important showing of his work was in 1947 and lasted for one week. During that week some fifteen thousand people visited the exhibition: an act of National homage. Since then, nearly half a century ago, little has been done to further his memory or to do him the credit and honor he deserves. The personality and life of Giuseppe Cali are important to anyone interested in his legacy. Cali was essentially a happy person. He had struggles, sorrows and fears to contend with, but his personality was jovial and optimistic: I have heard this from two of his daughters and from a number of his grandchildren (one of whom is my mother) who remember him. He took long walks daily and though he felt and loved his Italian blood and background (and indeed Italian was the language spoken in his household) he was prone to make the jocular toast after a successful sale, “God save the King, Money in my pocket, E viva Chamberlain.” Money in his pocket was a rare situation though, and his many children caused him financial hardship. He was known, on occasion, to borrow money in order to buy his friends a drink. Patrons did not always pay on time. Like so many people of talent or genius, Cali was not exempt of idiosyncrasy: he could play the piano in the grand waltz and polka style of the Belle Epoque, ad. libbing and composing as he went along, he suffered from the fear of the fury of the elements; this can be seen and observed in his pictures, and, if one knows about it, then it is clearly evident. Cali would climb into his wardrobe in a storm and would not come out until the thunder and lightning were gone. Perhaps his most charming quirk was to prepare himself for inspiration: he would take to his bed early one evening but not before having shaved and dressed in clean clothes ready for the morning. He would then go to sleep. At the crack of dawn, he would alight, his shoes already on, and head straight for a prepared canvas waiting on its easel, then without further ado, all his thoughts clear, his mind well rested, he would start a day’s hard work. I think it helps with the appreciation of Cali to like the man, and I hope that with the reading of this book his personality will emerge. He was a vibrant and a faithful gentle man with a ready sense of humor and a nervous system able to produce what must now be called patrimony. He is a national treasure: a man who has lived with a stout heart and left its resounding vibrations to inspire the people visiting his justifiably proud country. Nicholas de Piro

Referências específicas